skip to main |

skip to sidebar

The effort by the building industry to decarbonize the built environment has been underway for twenty years now. New York City, of all places, has made a commitment to reducing the carbon footprint of its existing structures, including its largest skyscrapers. Many of these examples were demonstrated at an APA Conference in the spring of 2001, called "Green Towers".

The effort by the building industry to decarbonize the built environment has been underway for twenty years now. New York City, of all places, has made a commitment to reducing the carbon footprint of its existing structures, including its largest skyscrapers. Many of these examples were demonstrated at an APA Conference in the spring of 2001, called "Green Towers".

In 2009, a $20 million eco-refit of the Empire State Building as an addition to its $500 million renovation was announced, and in 2011 that retrofit was completed. Tony Malkin leads a discussion of the project which involves a 3 year payback on operations and maintenance. And that doesn't include a an accounting of the savings in "embodied energy" of the existing iconic structure and keeping massive amounts of demolished material out of landfills.

Existing buildings are full of energy efficiency opportunities waiting to be realized. While some savings are obvious and easy to reach via one-off upgrades of windows, lighting and appliances, by using an integrated, whole-buildings design approach, profoundly larger energy savings can often be gained at little or no added capital cost. The efficiencies of many systems work together to create a drastic reduction in energy and water use.

The specifics of a deep retrofit are described here, as one of the initiatives established by the Rocky Mountain Institute. There's many tools on this site that help determine the best approaches to different recycling and retrofit issues with these older structures. It involves a whole process beginning with selecting the goals and going all the way through to measurement and verification of the resulting improved structure, thus completing a cycle of design and management.

In greater detail, the RMI has actually made available a complete white paper that discusses creative elements of deep whole building retrofits, published by ASHRAE. It's called "Whole-Building Retrofits: A Gateway to Climate Stabilization", by Victor Olgyay and Cherlyn Seruto. Olgyay is the author of the classic book, "Design With Climate" published in 1963. This approach has been evolving for decades, and the integration of natural principles, technological advancements and digital building managment has opened the door to an era of sustainable practices with the existing infrastructure of historic buildings. You couldn't build many of them today - the structures are the result of the kind of construction labor and material resources that you can't find today, hence the greater value in preserving and improving structures like this.

It's not just an old building anymore, it's a symbol of the new approach to the urban environment, that values what has gone before and conserves the heritage, the embodied energy and keeps that carbon out of the natural environment.

The above graphic is from the Environmental Law Institute, and illustrates a discussion of how the US Tax structure subsidizes foreign oil production, in 2009. Things have changed since then, and now polices are beginning to shift to support renewable energy sources. That, and conservation in many areas, have begun to take effect.

The above graphic is from the Environmental Law Institute, and illustrates a discussion of how the US Tax structure subsidizes foreign oil production, in 2009. Things have changed since then, and now polices are beginning to shift to support renewable energy sources. That, and conservation in many areas, have begun to take effect.

Which is a point emphasized by Amory Lovins and the RMI - the "think and do tank" - who takes the position that we can make this transition without further regulation by congress, by simply invoking the profit motive and efficiencies of scale. In promoting his book, he points out that China is currently the world leader in the use of renewables: photovoltaic, wind, small hydro, biogas, and solar thermal for hot water. This is evolving into a big, profitable business. Lovins goes right to the heart of the strategic argument for renewable energy as a standard:

In fact, to go back to the beginning of the modern climate debate, I think that when the bogus studies were issued claiming that climate protection would be very costly, the environmental movement fell into a trap of saying it won’t cost that much and it’s worth it. What they should have said is, “No, you’ve got it wrong. Climate protection is not costly but profitable because it’s cheaper to save fuel than to buy fuel.”

Lovins also delves into energy strategies that can be adopted immediately, such as net energy metering as well as addressing existing challenges for updating the US electrical grid to include all the issues that distributed systems of electricity create for the ratepayers as well as the utilities. The industry is evolving, and the integration of solar and wind power on an intelligent grid is becoming a fundamental shift from the old model of generated power from distant, dirty plants that also consume considerable amounts of water.

Yet the issue remains that public policy and taxation structures in the US and in other countries must necessarily be rapidly reformed to create even greater incentives for abandoning extractive energy sources. Going back to the global picture, these shifts in global taxes and incentives to renewables will be necessary to be in accord with agreed-to guidelines on carbon emissions by the countries around the globe. The US, being the largest contributor to global carbon over the last 200 years, will necessarily need to reduce its footprint extremely rapidly in order to get its per capita allowance under the probable caps. But if you look at it as Lovins does, it creates tremendous savings that can be applied to productive industries that propel economics forward under a different energy and development model. It's not a cost, it's an opportunity to create better solutions to human existence at a "profit" to those who undertake these challenges, since they'll not be burdened by the costs and responsibilities of carbon cleanup, toxic waste recapture, and a bunch of industrial "legacy" infrastructure.

A synergistic solution is something that's greater than the sum of its parts, and this is where collaboration and information exchange can leverage people and industries across the globe, since these interactions are the result of creativity and knowledge-sharing. Under these kinds of circumstances, constructive change can happen suddenly and in surprising ways. In the same way that no one dreamed of our current internet and global communication network fed by intelligent digtial technologies twenty years ago, there will be new people - driven social and communication structures that make many things possible within a decade that no one can even imagine today.

A future centered on the principles of life and a new view of managing energy could be the strategy that breaks out of the old structures that bind us to the destructive effects of carbon sources and the wars they create in the name of controlling resources for profit. These networks, being less territorial and more flexible than physical structures, could give way to a more vibrant way of existence for all of us.

The presentation above is from The UC Davis Chancellor’s Colloquium Series, a 45-minute presentation with question and answer for 30 minutes. It's presented by Ralph J. Cicerone, President of the National Academy of Sciences and Chair of the National Research Council. His expertise is in atmospheric chemistry, and he's one of the pre-eminent scientists speaking out on documented climate change in order to mitigate the increasingly critical impact of human activities on the global ecosystem.

In a nutshell, earth's climate is changing, as can be seen from measurements of rising air and water temperatures, decreasing amounts of polar ice and rising sea levels worldwide over the past three decades.Human-caused increases in atmospheric greenhouse gas concentrations, chiefly carbon dioxide from fossil-fuel combustion, are the likely cause of contemporary climate change. The rate of rise of carbon and greenhouse gasses has become frightening in the rapidity of change that's now being observed, particularly with the increasing rate of the melting of the polar ice caps. The changes in the last 50 years are unprecedented even in geological history.

The bathtub analogy is used to show how it's necessary to manage the global carbon dioxide cycle. The challenge of scale that it will take to reduce the carbon going into the ecosystem is daunting. Energy efficiencies are an approach that can be tackled immediately: greatly reducing oil and coal consumption through various strategies. Cicerone lays out approaches to geo-engineering that are possibilities that affect the factors of population, energy consumption and technology. A global per-capita emissions cap agreement (contraction and conversion model) seems to be the most necessary step in reversing the carbon impact that is projected in the future, particularly from developing countries.

Carbon capture doesn't seem to be a very viable part of the strategy; however, there are some steps being taken that produce possible solutions to creating more carbon sequestration. A big problem on the planet is the acidification of the oceans that results from the carbon absorption over the earth's seas that takes place as a result of increasing carbon levels. Research and examination of a science-based response to our impending self-inflicted catastrophe is critical. However, putting carbon genie back in the bottle is essentially a zero-sum game, once its released it takes eons to absorb it back into the global structure.

And time is of the essence; a 3 to 5 degree temperature rise in this century is inevitable, bringing us to the cusp of catastrophic climate change in the relatively near future.

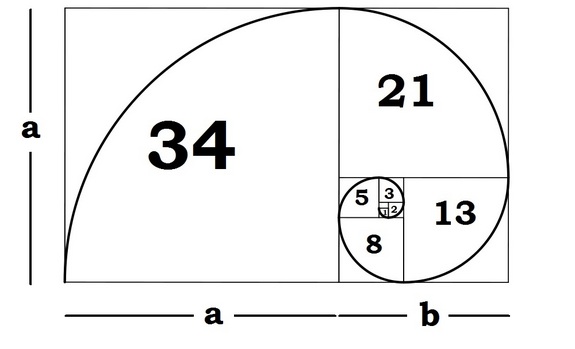

When journeying to places on this earth that establish a powerful sense of meaning and connection to the land, sky and water, one can always observe the intelligence of the structures built there as a response to the place. What we've lost in our modern urban cities and suburbs is a sense of how a place is rooted in its location, how it engages the sun and looks at the sky. Some of these places are sacred sites; some of them have been developed by earlier civilizations as a response to the land and water and also keyed to the constellations and solar and lunar solstices. They are the great mandalas, temples and pyramids that follow celestial patterns and embrace them with cultural meaning and intellectual patterns of response embodied in its form, whether it's the Golden Section of Greece or the mandalas of the far east. The ruins and temples of Peru, Bolivia, Egypt, Greece, Italy, Mexico, and so on are all grounded in an ancient world view that engages the earth with a mystic understanding of its patterns and flows, guided by older yet highly sophisticated observations of the solar and lunar cycles. These structures evolved over hundreds of years, expressing a timeframe that is beyond our comprehension; embedded in generational efforts to construct these massive places is the given culture and expression of mind that is alien to us now.

When journeying to places on this earth that establish a powerful sense of meaning and connection to the land, sky and water, one can always observe the intelligence of the structures built there as a response to the place. What we've lost in our modern urban cities and suburbs is a sense of how a place is rooted in its location, how it engages the sun and looks at the sky. Some of these places are sacred sites; some of them have been developed by earlier civilizations as a response to the land and water and also keyed to the constellations and solar and lunar solstices. They are the great mandalas, temples and pyramids that follow celestial patterns and embrace them with cultural meaning and intellectual patterns of response embodied in its form, whether it's the Golden Section of Greece or the mandalas of the far east. The ruins and temples of Peru, Bolivia, Egypt, Greece, Italy, Mexico, and so on are all grounded in an ancient world view that engages the earth with a mystic understanding of its patterns and flows, guided by older yet highly sophisticated observations of the solar and lunar cycles. These structures evolved over hundreds of years, expressing a timeframe that is beyond our comprehension; embedded in generational efforts to construct these massive places is the given culture and expression of mind that is alien to us now.

In Cambodia, Buddhist temples were built between the 9th and the 13th centuries by a succession of 12 Khmer kings. Angkor spreads over 120 square miles in South-East Asia and includes many major architectural sites. In 802, when construction began on Angkor Wat, financed by wealth from rice and trade, Jayavarman II took the throne, initiating an unparalleled period of artistic and architectural achievement, exemplified in the ruins of Angkor, center of the ancient empire. Here Angkor Wat, the world's largest temple, an extraordinarily complex structure filled with iconographic detail and religious symbolism, is sited. It was ultimately abandoned in the 15th century because of internecine rivalries and left to the ravages of time. It does, however, retain its orientation to the stellar axes and markers of the solstices; it's a means of orienting a holy form that serves the continual acknowledgement of deities and the stories of history, most markedly the Mahabharata and the Ramayana. The culture of South India has made its mark here; it's remarkable how the parts of the day are honored with the gods watching over all, prayers wafting to the sky.

Built in the later part of the 12th century by Jayavarman VII (the last king), Ta Prohm has been overtaken by jungle and is only now being slowly restored to its initial form. It has a smaller presence than the other temples, and is not as elaborate. The roots of the invading trees have crawled into the structure to the point that their removal would result in the collapse of the structure, so not all of this temple will be resurrected. It will remain firmly embedded in the Cambodian jungle as a reminder of an old civilization that failed to conquer the natural world for long and then passed into history. As have all the old civilizations. As will ours.

Update 3/24/16: The origins of Angkor Wat

The effort by the building industry to decarbonize the built environment has been underway for twenty years now. New York City, of all places, has made a commitment to reducing the carbon footprint of its existing structures, including its largest skyscrapers. Many of these examples were demonstrated at an APA Conference in the spring of 2001, called "Green Towers".

The effort by the building industry to decarbonize the built environment has been underway for twenty years now. New York City, of all places, has made a commitment to reducing the carbon footprint of its existing structures, including its largest skyscrapers. Many of these examples were demonstrated at an APA Conference in the spring of 2001, called "Green Towers".